I've moved my blog over here, to Wordpress, just because it looks so much nicer.

Please come over and say hello there.

Monday, 29 August 2016

Tuesday, 12 July 2016

Pigalle, then and now...

I have a new book coming out this week, set in Paris in 1899, and as a fair old chunk of it is set in the district of Pigalle, I thought it would be worth sharing one or two interesting things I came across during what I prefer to pass off as 'research'.

Paris, as everyone knows, is the city of light. But such simplicity can never be all there is to say about a place with such a long and intricate history, and Paris has its share of darker things too. For one hundred and fifty years, one area of the city has been synonymous with scandal, vice and covert thrills – Pigalle.

Today, the centreline of Pigalle – the Boulevard de Clichy – is commonly known as the sex district of Paris. It’s lined with garish vulgarity, and at Place Blanche is home to the most famous cabaret of all, the Moulin Rouge. In researching Mister Memory, however, I came across an almost forgotten world of strange cabarets and bizarre clubs in the area at the turn of the 19th to 20th centuries, and read about some things that could make one’s hair curl, even as jaded as we perhaps feel we are in the 21st century.

So which Pigalle is the more extreme? Which the naughtier? Which one would be more fascinating to spend an evening in? That of 2016, or that of 1899?

-

Where else to start but the Moulin Rouge? Opening in 1889, the Moulin has changed its nature several times over the course of 127 years. Originally it was conceived as a place in which the French Cancan (then called the Quadrille) could be danced, and if you’ve seen the Baz Luhrman film, you’ve had a closer glimpse of its original nature than you might have imagined. The Moulin was closely consulted by the filmmakers and one or two of its more outlandish features are based in reality.

|

| The façade of the Moulin Rouge, 1889 © Moulin Rouge |

|

| Le bal d'ouverture, 1889 © Moulin Rouge |

|

| Le 'Jardin de Paris', the Moulin Rouge © Moulin Rouge |

In fact, I was very firmly told that the Moulin’s official position is that they are not even in Pigalle, but the ‘foot of Montmartre’, not wishing to be associated with the more sordid sights to be found in the Boulevard. This makes the Moulin not so much an anachronism but an anatopism – something that is out of place, rather than out of time. If the Moulin were in the Champs Elysees, for example, as its main rival Le Lido is, no one would think twice about it.

Back at the end of the 19th century however, scandal often clung to the Moulin. Though topless dancers did not officially arrive in the district till 1920 (when a still-extant rival down the road, La Nouvelle Eve, started the trend) there would be from time to time something a little too much for polite Parisian society to ignore, for example, at the art student’s ball, Le Bal des Quat’z’Arts, of 1893, the presence of numerous nude women (and the occasional naked man) in parades depicting scenes from history and mythology was enough to result in a lawsuit.

|

| A dancer at the Moulin Rouge today © Moulin Rouge |

And all this is to say nothing of the near riots that the students themselves inaugurated as they wound their way up from the Latin Quarter to end up cavorting in Place Blanche, in full costume (such as gladiators, cavemen, Native Americans etc etc) and libated to an extreme. Accounts of such outings make wonderful reading in the biography of an American art student of the day entitled Bohemian Paris of Today, from which it’s clear that, at the time, some Parisians enjoyed the thrill of spending an evening in Pigalle, as distinct from an evening in Montmartre, which was also fun, but nothing like as scandalous. Or as dangerous. Pigalle was, at the time, home to ‘Les Apaches' – gangs of thugs who steamed down the boulevards, robbing or fighting, and were certainly to be feared. They had their own gang style, as did their women, who would often be pimped out by their own boyfriends.

The frisson of daring to rub shoulders with such people was all part of the ‘fun’ to be found in Pigalle, but there were other, more bizarre attractions too and the Moulin Rouge’s elephant was not the only strange site along the Boulevard de Clichy.

Some of the other places one might decide to venture into on an excursion to Pigalle were Heaven and Hell.

Here’s a closer look at Hell…

Yes, Saturday night might see you visit both the Cabaret du Ciel and the Cabaret d’Enfer, which were handily placed right next to each other. Inside each place patrons would be greeted by appropriate characters; St Peter or the Devil, for example, and sip themed drinks. The same spot today is a Monoprix (a cheap supermarket), which some local wits compare to Hell anyway.

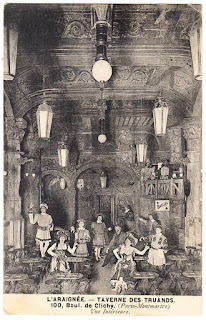

Just down the road was the Cabaret des Truands (‘hoodlums’) (today the Théâtre des Deux Ânes), which looked like this. . .

. . . and not too far away, my favourite; the Cabaret de Néant – the cabaret of nothingness, where customers would be assailed with a range of sights and experiences to make them ponder our flimsy mortality – lying in a coffin for a few brief moments being one of the attractions on offer.

You know an area has become hipster-level trendy when it gets its own four-letter acronym – Sopi (the network of streets South of Pigalle) may only have recently achieved this status but it’s long been an area of radical and varied nightlife. Opening its doors in 1897, in a dead-end alley off Rue Chaptal, the Théâtre du Grand Guignol was perhaps the most extreme of all the shows on offer, probably anywhere in the world, possibly ever. A sample of titles from the shows on offer will give a little indication of the horrific and sometimes downright bizarre fare on offer: The Dungeons; The Merchant of Microbes; Adultery; The Hanging; The Mark of the Beast among some of its more lurid pieces.

So which Pigalle is the more extreme – the one of today or of the late 19th century? Largely it depends on your point of view. Certainly it’s hard not to feel that today’s Boulevard de Clichy, for all its sex shops, the museum of eroticism etc, is rather one-dimensional and anodyne. It’s hard to think of anything less erotic than a ‘sex supermarket’, of which there are several along what it’s easy to think of as the Boulvard de Cliché. There are sex shows here, but little of anything that appears genuinely erotic, though that is after all such a personal matter.

It’s a view shared by local historian of Pigalle, Sylvanie de Lutèce. Working on archives in the Sorbonne, she’s researched the old times and the old shows, and works sometimes as a guide, sometimes as a producer of shows that hark back to something more real and honest. Once a month or so, a group or performers gather upstairs at Le Pigalle brasserie on the north side of Place Pigalle to perform routines that might not have been out of place a hundred years ago.

Here, they dance the Cancan in the traditional way, a dance that Sylvanie points out was originally full of meaning, and political meaning at that – the various poses of the dance symbolising, and mocking, all sorts of establishment figures; legs joined in an arch represented the Church, legs held (rather impressively) up at the shoulder stood for the soldier at arms, and so on. None of this, of course, is known to the causal visitor to Pigalle or the Moulin Rouge today. Sylvanie thinks that’s a great shame, and is happy to talk to us for a long time about the area, and the way in which it’s changed. And is still changing, though one thing remains true across the decades; this has always been a defiant corner of the city. ‘Pigalle,’ she says, ‘is not a easy girl’.

As yet, there’s not so much sign of the rapid recent gentrification of the area that Soho in London has seen. But it’s on its way; as rents rise and as more ‘respectable’ enterprises creep eastwards along from Place du Clichy, the area will certainly change. That’s something that both the Moulin Rouge and Sylvanie de Lutèce will appreciate. The Moulin will no longer find itself stranded in a seedy sea of sex shops, and there’ll be more tourists willing to come and find more creative performances, plays, mise-en-scènes and the like by Sylvanie and her friends, things that might remind us of the wonderful variety, now long gone, but which was once upon a time found in Pigalle.

|

| Le Ciel and L'Enfer cabarets |

|

| L'Enfer cabaret, Pigalle, early 19th century |

|

| Cabaret des Truands - exterior |

|

| Cabaret des Truands - interior |

|

| The third 'cave' of the Cabaret du Néant |

The raison-d’être of the theatre was to perform plays to shock and amaze, and if no one fainted, was sick, or left during the evening, they hadn’t been doing their job properly. The work of the Théâtre du Grand Guignol predates the advent of extreme horror films by several decades, and great use was made of all kinds of special effects to simulate (we hope) torture, branding with hot irons, the letting of blood and even acid attacks to the face. Such was the realism of these effects that barely a night passed without incident in the audience, either in horror, or outrage – another signature tactic was the risqué nature of some pieces, frequently pushing the boundaries of how much nudity was permissible. Unlike so many of the other cabarets and theatres of the time, this one is still at least a theatre, and a good one at that; the International Visual Theatre.

|

| The International Visual Theatre, once the site of the Grand Guignol |

|

| Upstairs at Le Pigalle |

My thanks to Sylvanie de Lutèce, and Fanny Rabasse of the Moulin Rouge.

Kubrick again...

I wrote a while back on the Kubrick exhibition that's steadily making its way around the globe, and what a treat it is for the fan of the great filmmaker.

That show still hasn't come to London, but I went to see the new Daydreaming with Stanley Kubrick yesterday, at Somerset House, and am reporting back to anyone interested and wondering whether it's worth the trip. The show is described as a 'new exhibition, curated by Mo’Wax and UNKLE founder, artist and musician James Lavelle, featuring a host of contemporary artists, film makers and musicians showcasing works inspired by Stanley Kubrick.'

Interesting idea, but are the results any good?

Having been advised to pre-book a ticket, I thought the place might be rammed. As you can see from the picture above, it was pretty quiet and one could have just wandered in without a reservation. It was good that it was so empty, from the visitor's point of view, because many of the pieces in the show are immersive installations that really benefit from being alone in them.

Here's the second thing you see (the first being a portrait of the man in question by his wife, Christiane):

This piece, by Mat Collinshaw, projects the face of a chimp over the image of a skull, all inside a space helmet. It's called Alpha-Omega and is of course a response to 2001.

Beyond this subtle beginning to the show, you enter this corridor, which fans of The Shining will appreciate:

Around 20 rooms line this spine of the show, containing a total of 45 pieces of work. Some are very explicit references to Kubrick works, some less so, and take a moment or two to spot the connection to the film (or films) being alluded to.

Here are one or two pieces I enjoyed the most.

Room 7 (and it's a shame they didn't contrive a room 237) contains work by James Lavelle himself, amongst others, and includes this oversized teddybear referencing A Clockwork Orange, as well as numerous boxes from Jack's imprisonment in the pantry of The Overlook hotel. The colour in this photo is more or less accurate, the room being lit by eerie red neon.

Visual and aural disturbance is a clear theme in the show, with many pieces reflecting this nature of much of Kubrick's work. There's a room by Haroon Mirza and Anish Kapoor for example, which I challenge you to stand in for more than a minute with your eyes open. Strobing light and sound producing nausea rather rapidly, if not entirely meaningfully.

However, just at the end of the corridor nearby, is this:

...And the second one was this, by Jane and Louise Wilson, based on one of the most famous of the movies that Kubrick never managed to make; Aryan Papers. Using stills from Kubrick's infamously intensive research process, the Wilsons simply project image after image with a simple voiced description of what the photo contains. Many of the images and film clips are of Kubrick's chosen actress, Johanna ter Steege.

This is a terrible photograph of something it's impossible to capture in a still shot anyway - it's a strobing LED light which is rather blinding in the darkness where it lies. There doesn't seem much to it, so you look away quite quickly, and that's when something weird happens. As you look away, a ghostly image flashes into your vision so fast it's hard to be sure you haven't imagined it. But repeating the experiment proves it - for the LED is designed to project a face into your peripheral vision, meaning you only see it as you glance away. The face is, of course, that of SK himself, immediately recognisable once seen.

In fact, Kubrick's face (and in one case, whole body encased in snow), is another recurring them of the show. And why not? It's nice to be reminded of the man behind the lens.

The two rooms I enjoyed the most were, firstly, this one, by Doug Foster, which is not the slitscan sequence from 2001, but a modern version of it, and very beautiful it is too. Sitting on a bench in a dark room, it would be easy to while away a couple of hours in a trance in front of it.

...And the second one was this, by Jane and Louise Wilson, based on one of the most famous of the movies that Kubrick never managed to make; Aryan Papers. Using stills from Kubrick's infamously intensive research process, the Wilsons simply project image after image with a simple voiced description of what the photo contains. Many of the images and film clips are of Kubrick's chosen actress, Johanna ter Steege.

What lifts this simple idea to something mesmerizing are the mirrors on either side of the projected images, leading to a curving infinite repetition on both sides as you gaze at Kubrick's work in progress. When the shots becomes those of Jews in the ghettos of Poland, and one thinks of the horror that befell many, many individuals, the weight of this infinite repetition starts to give a tremendously unsettling tone.

In brief, yes, if you're a Kubrick fan, and can make the trip to London easily enough, it's worth the time spent. While some pieces feel overly contrived and lacking power, many are successful, to me at least, and pleasingly develop ideas and emotions you feel while watching the films. That's surely the aim of a show like this. But I still want the Tour itself to come to London...

Wednesday, 29 June 2016

My six favourite European novels

I am supposed to be working on something else (quite urgent) this morning, but the open letter from Mr B's Emporium of Books has urged me to write this post instead, because nothing else seems as urgent right now. (This post is unashamedly personal, and contains public displays of political affiliation, as well as affection).

-

I have been in one of those pessimistic moods of late (and this was before last Thursday), where I question the value of being a writer; that my job doesn't save lives, or put fires out, or shape economic policy. It's one of those times where I can't shake Mishima's statement that the writer is the ultimate voyeur; that we sit around on the fringes of the action, making prurient notes in our notebooks, and then spilling our thoughts, whether they be of schadenfreude, or of joie de vivre, for our own private benefit.

I am lucky. My father founded and ran a group of EFL schools in Kent in the 60s, 70s and 80s. Since my mother worked there too and since my parents couldn't afford a baby sitter, my brother and I would often happily be dragged along to functions of various kinds. I'm sure they felt it was good for us to meet people from other cultures, growing up as we did in a very white part of England, but the accidental wisdom of this cannot be underestimated. My brother and I would stand around while we were shyly introduced to young students from around the world who'd come to learn English at my Dad's schools. I have fond memories of meeting many German, French, Italian, Swedish, Russian and Greek students amongst others from Europe, as well as people from further away: Iranians, Iraqis, Saudis, Nigerians, Egyptians, Japanese and so on and so on, and without fail, all I can remember are happy faces, warm smiles, and friendly handshakes. I learnt very early on that there is nothing to fear in the Other, per se; that there are kind and generous people across the world.

So today, and focussing for obvious reasons on Europe, here are my favourite European novels.

FINLAND (written in Swedish)

The Summer Book - Tove Jansson

As wonderful as Jansson's Moomin books are, my favourite of her works are The Summer Book and The Winter Book - both depicting life on one of the myriad small islands in the Baltic between Sweden and Finland, and the relationship between an elderly artist and her granddaughter. Somewhat autobiographical, utterly touching, with deceptively simple writing that lingers long.

ITALY

Foucault's Pendulum

His best known novel is perhaps The Name of the Rose, and as 'fun' as that book is, Eco's ability to combine elements of the thriller, the literary novel and historical fiction are never better displayed in this story that's what the Da Vinci code might be if it was (way) smarter and had its tongue in its cheek. The book every tin-foiling, bunker-building, survivalist-loving conspiracy theorist ought to read.

FRANCE

The Outsider - Albert Camus

Sadly, I have only ever managed to read a handful of books in their original language, one being The Summer Book, above, and another being this classic French novel of existential horror, and simmering racism. You'll notice that what links them both is that they are very short. But short novels are often the most powerful - their content is distilled, and hit you harder as a result.

SWITZERLAND

The Vampire of Ropraz - Jacques Chessex

Loosely based on the true story of a serial killer in the Jura Mountains in the early days of the 20th century, this is another short book that punches above its weight, using distancing prose in an almost reportage style that somehow makes the events it describes even more horrific.

POLAND

Who was David Weiser? - Paweł Huelle

So much more than a coming of age story - this mysterious tale is a book about tolerance, friendship and faith. Set in the Poland of the late fifties, a country still very much living with the outcomes of war, it's the story of a strange, charismatic boy with powers no one understands and whose disappearance is never satisfactorily solved.

GERMANY

The Magic Mountain - Thomas Mann

In my humble estimation, this is the finest novel ever written and I am going to say nothing about it (or we'll be here all day) apart from the thought that this masterpiece is set in the seven years up to 1914 and therefore the approach of war that will see Europe run with an ocean of blood – to paraphrase Jung's nightmare that was a premonition of European conflict – is never too far away. Look away now if you don't want to read the final line of the book (in the translation by H.T. Lowe-Porter).

"Out of this universal feast of death, out of this extremity of fever, kindling the rain-washed evening sky to a fiery glow, may it be that Love one day shall mount?"

Think it's too much to intimate that we could see war again in Europe? That's what they said after the war Mann was writing about. It's what we said after the second war too. And after that horror, we founded a European community in which conflicts would be settled in debating chambers and courtrooms, as opposed to gas chambers and battlefields. Actual warfare was assumed to be a thing of the past, and then came the genocides of the wars in the former Yugoslavia, and that was only 20 odd years ago.

To end, I've just returned from the American Librarian Association's conference. It was heartening to see how many people were not follwing the EU referendum, but as horrified (and amazed) by the result. They see the obvious implication for their looming presidential election this November, and realise that the same mentality that voted to leave is the same mentality that may elect a ranting racist to the most powerful job in the world. Driven by the same kind of fear-mongering, this is a mindset that refuses to accept that we live in a globally-connected world. We can either enjoy and profit from that cross-culturality, or we can live in fear and conflict.

Had my father lived, (he would have been 100 this year, born during a Zeppelin raid in the first world war), he would be weeping to see the events of the last few weeks. When he died, my mother asked me to sketch a design for a sundial to be set in the grounds of the college he created. The block of slate was duly made in Wales, and dispatched to Kent, inscribed with words she chose; under his name and dates is the following: 'This centre of international friendship is his memorial'. His was work that I find it easy to see as important - not only did his schools teach people English, I saw how they fostered tolerance and understanding.

In my jet-lagged haze, I am trying to tell myself that books are important. That they do have a place in all this; that perhaps, in the long run, they really are the most potent force of all, because they contain ideas, ideas that can change the planet. We know this to be true, or freedom of speech wouldn't be banned in more than half the nations on Earth. As Percy Shelley said, 'poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world'.

So who's right - Mishima or Shelley? Are writers insensitive voyeurs, or honourable philosophers? I guess my view on this can be summed up in this thought about writing by another poet, John Keats, who said a writer spends his or her life trying to work out whether they are the healer or the patient.

The answer, of course, is both.

Monday, 6 June 2016

Saint Death

Saint Death plays out on the borderland of Mexico and the USA. It's the story of Arturo, who has one night to play a deadly card game to save his friend Faustino's life – Faustino having fallen into working for a street gang in Juarez, connected to the drug trade.

It's a story about power, lies, and friendship, and it's about what happens we be build fences between rich communities and poor ones, and then try to pass things of value (i.e. drugs, guns etc) across those borders.

Hovering in the background, never too far away, is the mysterious figure of Santa Muerte, (Holy or Saint Death), a 'folk saint' of growing popularity in Mexico and parts of the US. She's a figure of disputed origins and disputed significance, and is worshipped by many different people from all sectors of society: the poor, the powerful, drug lords, prisoners, prison officers, police, prostitutes... the list goes on and on. If you're interested to find out more, this video from youtube is as good a summary as any of the 'white lady' (who goes by many, many names).

There's some confusion over the various icons of death that Mexico employs.

Santa Muerte is a (female) skeleton in a shroud, often depicted holding a scythe in one hand and the world in the other (the scythe suggests the more European-in-origin figure of the Grim Reaper but the 'bony girl' is a distinct personality).

(Other figures, such as general 'calavera' (skull) icons like the one on the cover of my book, and the girl known as La Catrina, are also separate entities.)

You can read an extract from Saint Death on The Guardian's website. It will be published on October 6th 2016 in the UK and April 2017 in the USA.

Thursday, 26 May 2016

The Ghosts of Heaven - cipher solved

This post is probably only of interest to anyone who got to the end of The Ghosts of Heaven and wondered what the page of numbers and letters at the end of the book was all about; the page in question being this:

A lot of people wrote to me, asking if it was a cipher, and in response to that, I posted this in April of 2015, just over a year ago, and around eight months after the first publication of the book in the UK. In short; yes, I said, it is a cipher, and no, I'm not going to give any clues about how to solve it; other than stipulating that everything need to solve the thing could be found in the book itself.

I wasn't giving clues because I like being mean, in fact it was very hard sticking to what I had decided; namely that I wanted to see how long it would take for someone to solve the cipher with no help from me at all, and I could be certain that help could come from nowhere else because no one (not even my editors nor family) knew what it was all about. (Note, you can only get away with this kind of thing if your editors trust you).

It was, therefore, with great happiness a couple of days ago that I received an email from one Erik Kjellgren of Texas, because he's cracked it: he sent me the solution. So as to give him full credit for his work, I asked him for his own words on how he did it:

"Whenever I read a book I have this habit of reading all of the additional information inside of it before beginning on the main content. In the case of The Ghosts of Heaven, this involved your spiral definition, the introduction, and turning to the back to see the cipher you had left. At the time I didn’t think much of it, maybe assuming it to be an unnecessary filler page, and so began reading. I didn’t think of the cipher again until I reached page 310, and a series of artists were mentioned. I took AP Art History this last year and we learned, of course, about Van Gogh, Rembrandt, and The Spiral Jetty. I was completely unaware of Final Words by Rijndael, and so I googled it, only to find the Rijndael Key Schedule. I read through the Wikipedia page and was reminded of the final page of the book. I then googled “The Ghosts of Heaven Code” and was led to your blog post, saw your warning, and saw your hint of it all being available in the book. This basically confirmed for me that I was on the right track. I then googled “Rijndael Decipher”, and found http://rijndael.online-domain-tools.com/ (honestly this felt like cheating, but I can’t imagine anybody deciphering that code by hand). Using that resource, I realized that I only needed the mode and the key. I decided to skim over the beginning of the third quarter to see if I had missed something, and saw that it was said on page 290 that a woman had a “CBC of at least 256”. CBC was clearly what I needed for the mode, and because of this I also needed the initial vector in addition to the key. The key was easy, however. From the Wikipedia page I knew I needed a 16-digit key, and on page 321 Bowman gives a code of the first 16-digits of Phi. I decided that must have been the key (quite fitting seeing as Phi is sort of the key to the entire novel). I assumed the initial vector to be zero just out of hope, ended up being correct, and was able to put in the characters from that page 256 digits at a time to reveal the message."

This makes me very happy, as I said, because this are exactly the steps I hoped someone might take to figure it out, and Erik explains it all so succinctly there is nothing left for me to add. Except, perhaps, the solution itself... which is no great earth-shattering secret, just something I was thinking as I wrote the book, but nevertheless something which I hope makes the bleaker parts of it, and life, seem much less so.

"'The best people possess a feeling for beauty, the courage to take risks, the discipline to tell the truth, the capacity for sacrifice. Ironically, their virtues make them vulnerable; they are often wounded, sometimes destroyed..' So said a writer whose work has always been important to me. I would only add one thing; there are those who are destroyed, those for whom life is simply too strong, but as long as they are remembered in the hearts of their loved ones, they shall not die, but shall live forever..."

Not that I'd offered one, but a small prize is being dispatched to Texas very soon. Thanks, Erik, for making my day.

A lot of people wrote to me, asking if it was a cipher, and in response to that, I posted this in April of 2015, just over a year ago, and around eight months after the first publication of the book in the UK. In short; yes, I said, it is a cipher, and no, I'm not going to give any clues about how to solve it; other than stipulating that everything need to solve the thing could be found in the book itself.

I wasn't giving clues because I like being mean, in fact it was very hard sticking to what I had decided; namely that I wanted to see how long it would take for someone to solve the cipher with no help from me at all, and I could be certain that help could come from nowhere else because no one (not even my editors nor family) knew what it was all about. (Note, you can only get away with this kind of thing if your editors trust you).

It was, therefore, with great happiness a couple of days ago that I received an email from one Erik Kjellgren of Texas, because he's cracked it: he sent me the solution. So as to give him full credit for his work, I asked him for his own words on how he did it:

"Whenever I read a book I have this habit of reading all of the additional information inside of it before beginning on the main content. In the case of The Ghosts of Heaven, this involved your spiral definition, the introduction, and turning to the back to see the cipher you had left. At the time I didn’t think much of it, maybe assuming it to be an unnecessary filler page, and so began reading. I didn’t think of the cipher again until I reached page 310, and a series of artists were mentioned. I took AP Art History this last year and we learned, of course, about Van Gogh, Rembrandt, and The Spiral Jetty. I was completely unaware of Final Words by Rijndael, and so I googled it, only to find the Rijndael Key Schedule. I read through the Wikipedia page and was reminded of the final page of the book. I then googled “The Ghosts of Heaven Code” and was led to your blog post, saw your warning, and saw your hint of it all being available in the book. This basically confirmed for me that I was on the right track. I then googled “Rijndael Decipher”, and found http://rijndael.online-domain-tools.com/ (honestly this felt like cheating, but I can’t imagine anybody deciphering that code by hand). Using that resource, I realized that I only needed the mode and the key. I decided to skim over the beginning of the third quarter to see if I had missed something, and saw that it was said on page 290 that a woman had a “CBC of at least 256”. CBC was clearly what I needed for the mode, and because of this I also needed the initial vector in addition to the key. The key was easy, however. From the Wikipedia page I knew I needed a 16-digit key, and on page 321 Bowman gives a code of the first 16-digits of Phi. I decided that must have been the key (quite fitting seeing as Phi is sort of the key to the entire novel). I assumed the initial vector to be zero just out of hope, ended up being correct, and was able to put in the characters from that page 256 digits at a time to reveal the message."

This makes me very happy, as I said, because this are exactly the steps I hoped someone might take to figure it out, and Erik explains it all so succinctly there is nothing left for me to add. Except, perhaps, the solution itself... which is no great earth-shattering secret, just something I was thinking as I wrote the book, but nevertheless something which I hope makes the bleaker parts of it, and life, seem much less so.

"'The best people possess a feeling for beauty, the courage to take risks, the discipline to tell the truth, the capacity for sacrifice. Ironically, their virtues make them vulnerable; they are often wounded, sometimes destroyed..' So said a writer whose work has always been important to me. I would only add one thing; there are those who are destroyed, those for whom life is simply too strong, but as long as they are remembered in the hearts of their loved ones, they shall not die, but shall live forever..."

Not that I'd offered one, but a small prize is being dispatched to Texas very soon. Thanks, Erik, for making my day.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)